Retinal Detachment

What is the retina?

What is a retinal detachment?

What are the signs and symptoms of a retinal detachment?

What are the risk factors for developing a retinal detachment?

Which diseases of the eyes predispose to the development of a retinal detachment?

How does cataract surgery lead to a retinal detachment?

What other factors are associated with a retinal detachment?

Why is it mandatory to treat retinal detachments?

How are detached retinas repaired?

What are the complications of surgery for a retinal detachment?

What are the results of surgery for a retinal detachment?

What is the retina?

The retina is an extremely thin tissue that lines the inside of the back of the eye. When we look around, light from the objects we are trying to see enters the eye. The light image is focused onto the retina by the cornea and the lens.

The retina is about the size of a postage stamp. It consists of a central area called the macula and a much larger peripheral retina.

The macula is a small central area of the retina that contains a high concentration of vision receptors. Accordingly, it enables clear central vision to see fine details for such activities as reading or threading a needle.

What is a retinal detachment?

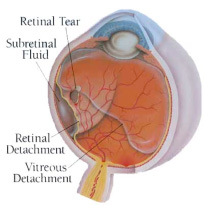

A retinal detachment is a separation of the retina from its attachments to its underlying tissue within the eye. Most retinal detachments are a result of a retinal break, hole, or tear. These retinal breaks may occur when the vitreous gel pulls loose or separates from its attachment to the retina, usually in the peripheral parts of the retina. The vitreous is a clear gel that fills 2/3 of the inside of the eye and occupies the space in front of the retina. As the vitreous gel pulls loose, it will sometimes exert traction on the retina, and if the retina is weak, the retina will tear. Most retinal breaks are not a result of injury. Retinal tears are sometimes accompanied by bleeding if a retinal blood vessel is included in the tear.

Once the retina has torn, liquid from the vitreous gel can then pass through the tear and accumulate behind the retina. The build-up of fluid behind the retina is what separates (detaches) the retina from the back of the eye. As more of the liquid vitreous collects behind the retina, the extent of the retinal detachment can progress and involve the entire retina, leading to a total retinal detachment. A retinal detachment almost always affects only one eye. The second eye, however, must be checked thoroughly for any signs of predisposing factors that may lead to detachment in the future.

What are the signs and symptoms of a retinal detachment?

Flashing lights and floaters may be the initial symptoms of a retinal detachment or of a retinal tear that precedes the detachment itself. Anyone who is beginning to experience these symptoms should see an eye doctor (ophthalmologist) for a retinal exam. In the exam, drops are used to dilate the patient's pupils to make a more detailed exam easier. The symptoms of flashing lights and floaters may often be unassociated with a tear or detachment and can merely result from a separation of the vitreous gel from the retina. This condition is called a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). Although a PVD occurs commonly, there are no tears associated with the condition most of the time.

The flashing lights are caused by the vitreous gel pulling on the retina or a looseness of the vitreous, which allows the vitreous gel to bump against the retina. The lights are often described as resembling brief lightning streaks in the outside edges (periphery) of the eye.

The floaters are caused by condensations (small solidifications) in the vitreous gel and frequently are described by patients as spots, strands, or little flies. Some patients even want to use a flyswatter to eliminate these pesky floaters. There is no safe treatment to make the floaters disappear. Floaters are usually not associated with tears of the retina.

If the patient experiences a shadow or curtain that affects any part of the vision, this can indicate that a retinal tear has progressed to a detached retina. In this situation, one should immediately consult an eye doctor since time can be critical.

The goal for the ophthalmologist is to make the diagnosis and treat the retinal tear or detachment before the central macular area of the retina detaches.

What are the risk factors for developing a retinal detachment?

Studies have shown that the incidence of retinal detachments caused by tears in the retina is fairly low, affecting approximately one in 10,000 people each year. Many retinal tears do not progress to retinal detachment. Nevertheless, many risk factors for developing retinal detachments are recognized, including certain diseases of the eyes (discussed below), cataract surgery, and trauma to the eye. Retinal detachments can occur at any age. They occur most commonly in younger adults (25 to 50 years of age) who are highly nearsighted (myopic) and in older people following cataract surgery

Which diseases of the eyes predispose to the development of a retinal detachment?

Lattice degeneration of the retina is a type of thinning of the outside edges of the retina, which occurs in 6%-8% of the general population. The lattice degeneration, so-called because the thinned retina resembles the crisscross pattern of a lattice, often contains small holes. Lattice degeneration is more common in patients with nearsightedness (myopia). This tendency to lattice degeneration occurs because myopic eyes are larger than normal eyes and, therefore, the peripheral retina is stretched more thinly. Fortunately, only about 1% of patients with lattice degeneration go on to develop a retinal detachment.

High myopia (greater than 5 or 6 diopters of nearsightedness) increases the risk of a retinal detachment. In fact, the risk increases to 2.4% as compared to a 0.06% risk for a normal eye at age 60. (Diopters are units of measurement that indicate the power of the lens to focus rays of light.) Cataract surgery or other operations of the eye can further increase this risk in patients with high myopia.

Patients taking certain eye drops have an increased risk of developing a retinal detachment. Pilocarpine (Salagen), which for many years has been a mainstay of therapy for glaucoma, has long been associated with retinal detachment. Moreover, by constricting the pupil, pilocarpine makes the diagnostic exam of the peripheral retina more difficult, possibly leading to a delay in the diagnosis.

Patients with chronic inflammation of the eye (uveitis) are at increased risk of developing retinal detachment.

How does cataract surgery lead to a retinal detachment?

Cataract surgery, especially if the operation has complications, increases the risk of a retinal detachment. Cataracts are areas of cloudiness (opacities) that form in the lens. Following the introduction of extracapsular surgery, a modern method used almost exclusively today for the removal of cataracts, the risk of retinal detachment became far less. In extracapsular cataract surgery, part of the capsule of the lens is left in place so that the vitreous gel is undisturbed.

Phacoemulsification is a type of extracapsular cataract surgery that utilizes a very high speed ultrasonic instrument to break up and suck out the clouded lens of the eye. The capsule that is left in the eye may at a later time become cloudy, necessitating opening the capsule by using a laser. Opening the capsule increases the risk of retinal detachment.

In intracapsular cataract surgery, the predominant surgical method used from 1965 to 1990, the entire lens was removed. The capsule at the back of the lens, therefore, was no longer present to hold the vitreous gel in place. Consequently, the vitreous gel moved forward, and the retina was subjected to increased pulling or traction on the retina from the vitreous, which led to tears of the retina. Today, if the capsule is broken, which can be a complication during extracapsular cataract surgery, the vitreous gel similarly can move forward and pull on the retina. This sequence can lead to a retinal tear and a detachment, especially during the first year after surgery.

What other factors are associated with a retinal detachment?

- Blunt trauma, as from a tennis ball or fist, or a penetrating injury by a sharp object to the eye can lead to a retinal detachment.

- A family history of a detached retina that is non-traumatic in nature seems to indicate a genetic (inherited) tendency for developing retinal detachments.

In as many as 5% of patients with a non-traumatic retinal detachment of one eye, a detachment subsequently occurs in the other eye. Accordingly, the second eye of a patient with a retinal detachment must be examined thoroughly and followed closely, both by the patient and the ophthalmologist.

Diabetes can lead to a type of retinal detachment that is caused by pulling on the retina (traction) alone, without a tear. Because of abnormal blood vessels and scar tissue on the retinal surface in some patients with diabetes, the retina can be lifted off (detached) from the back of the eye. In addition, the blood vessels may bleed into the vitreous gel. This detachment may involve either the periphery or central area of the retina.

Why is it mandatory to treat a retinal detachment?

A tear or hole of the retina that leads to a peripheral retinal detachment causes the loss of side (peripheral) vision. Almost all of these patients will progress to a full retinal detachment and loss of all vision if the problem is not repaired. The dark shadow or curtain obscuring a portion of the vision, either from the side, above, or below, almost invariably will advance to the loss of all useful vision. Spontaneous reattachment of the retina is rare.

Early diagnosis and repair are urgent since visual improvement is much greater when the retina is repaired before the macula or central area is detached. The surgical repair of a retinal detachment is usually successful in reattaching the retina, although more than one procedure may be necessary. Once the retina is reattached, vision usually improves and then stabilizes. Successful reattachment does not always result in normal vision. The ability to read after successful surgery will depend on whether or not the macula (central part of the retina) was detached and the extent of time that it was detached.

How are detached retinas repaired?

Retinal holes or tears can be treated with laser therapy or cryotherapy (freezing) to prevent their progression to a full-scale detachment. Many factors determine which holes or tears need to be treated. These factors include the type and location of the defects, whether pulling on the retina (traction) or bleeding is involved, and the presence of any of the other risk factors discussed above.

Three types of eye surgery are done for actual retinal detachment: scleral buckling, pneumatic retinopexy, and vitrectomy.

Scleral buckling

For many years, scleral buckling has been the standard treatment for detached retinas. The surgery is done in a hospital operating room with general or local anesthesia. Some patients stay in the hospital overnight (inpatient), while others go home the same day (outpatient). The surgeon identifies the holes or tears either through the operating microscope or a focusing headlight (indirect ophthalmoscope). The hole or tear is then sealed, either with diathermy (an electric current which heats tissue), a cryoprobe (freezing), or a laser. This results in scar tissue later forming around the retinal tear to keep it permanently sealed, so that fluid no longer can pass through and behind the retina. A scleral buckle, which is made of silicone, plastic, or sponge, is then sewn to the outer wall of the eye (the sclera). The buckle is like a tight cinch or belt around the eye. This application compresses the eye so that the hole or tear in the retina is pushed against the outer scleral wall of the eye, which has been indented by the buckle. The buckle may be left in place permanently. It usually is not visible because the buckle is located half way around the back of the eye (posteriorly) and is covered by the conjunctiva (the clear outer covering of the eye), which is carefully sewn (sutured) over it. Compressing the eye with the buckle also reduces any possible later pulling (traction) by the vitreous on the retina.

A small slit in the sclera allows the surgeon to drain some of the fluid that has passed through and behind the retina. Removal of this fluid allows the retina to flatten in place against the back wall of the eye. A gas or air bubble may be placed into the vitreous cavity to help keep the hole or tear in proper position against the scleral buckle until the scarring has taken place. This procedure may require special positioning of the patient's head (such as looking down) so that the bubble can rise and better seal the break in the retina.

Pneumatic retinopexy

Pneumatic retinopexy is a newer method for repairing retinal detachments. It usually is performed on an outpatient basis under local anesthesia. Again, laser or cryotherapy is used to seal the hole or tear. The surgeon then injects a gas bubble directly inside the vitreous cavity of the eye to push the detached retina against the back outer wall of the eye (sclera). The gas bubble initially expands and then disappears over two to six weeks. Proper positioning of the head in the postoperative time period is crucial for success. Although this treatment is inappropriate for the repair of many retinal detachments, it is simpler and much less costly than scleral buckling. Furthermore, if pneumatic retinopexy is unsuccessful, scleral buckling still can be performed.

Vitrectomy

Certain complicated or severe retinal detachments may require a more complicated operation called a vitrectomy. These detachments include those that are caused by the growth of abnormal blood vessels on the retina or in the vitreous, as occurs in advanced diabetes. Vitrectomy also is used with giant retinal tears, vitreous hemorrhage (blood in the vitreous cavity that obscures the surgeon's view of the retina), extensive tractional retinal detachments (pulling from scar tissue), membranes (extra tissue) on the retina, or severe infections in the eye (endophthalmitis).

Vitrectomy surgery is performed in the hospital under general or local anesthesia. Small openings are made through the sclera to allow positioning of a fiberoptic light, a cutting source (specialized scissors), and a delicate forceps. The vitreous gel of the eye is removed and replaced with a gas to refill the eye and reposition the retina. The gas eventually is absorbed and is replaced by the eye's own natural fluid. A scleral buckle is usually also performed with the vitrectomy

What are the complications of surgery for a retinal detachment?

Discomfort, watering, redness, swelling, and itching of the affected eye are all common and may persist for some time after the operation. These symptoms are usually treated with eye drops. Blurred vision may last for many months, and new glasses may need to be prescribed, especially because the scleral buckle may have changed the shape of the eye. The scleral buckle also can cause double vision (diplopia) by affecting one of the muscles that controls the movements of the eye.

Other complications can include elevated pressure in the eye (glaucoma), bleeding into the vitreous, within the retina or behind the retina, clouding of the lens of the eye (cataract), or drooping of the eyelid (ptosis). Additionally, infection can occur around the scleral buckle or even more widely in the eye (endophthalmitis). Occasionally, the buckle may need to be removed.

What are the results of surgery for a retinal detachment?

The surgical repair of retinal detachments is successful in about 80% of patients with a single procedure. With additional surgery, over 90% of retinas are reattached successfully. Several months may pass, however, before vision returns to its final level. The final outcome for vision depends on several factors. For example, if the macula was detached, central vision rarely will return to normal. Even if the macula was not detached, some vision may still be lost, although most will be regained. New holes, tears, or pulling may develop, leading to new retinal detachments. If a gas or air bubble was inserted in the eye during surgery, maintaining proper positioning of the head is also important in determining the final outcome. Close follow-up by an ophthalmologist, therefore, is required.

Long-term studies have shown that even after preventive treatment of a retinal hole or tear, 5% to 9% of patients may develop new breaks in the retina, which could lead to a retinal detachment. Overall, however, repair of retinal detachments has made great strides in the past 20 years with the restoration of useful vision to many thousands of patients.